Physician Dispensing and Opioid Abuse: Drug Dilemma Prevention Strategies

When it comes to challenges in workers’ compensation pharmacy, the industry trends are surprisingly similar year after year. Over the past few years, the issues of physician dispensing and opioid abuse have been in the national spotlight. High profile arrests for physician-dispensed kickbacks, new state opioid prescribing limit laws and the federal government’s approval of an omnibus bill aimed at treatment and prevention of opioid abuse illustrate that these important issues are on the minds of leaders across the country and not just in the workers’ compensation industry. These are challenging problems to tackle; however, insights from data, appropriate communication and effective programs provide the industry the opportunity to improve outcomes for all.

Physician Dispensing

Physician dispensing has been a challenge for the industry for more than a decade. In the past few years, it has taken on greater importance due to declining reimbursement rates for medical services, skyrocketing costs of products targeted to physicians for office dispensing, and the rise of opioid abuse. The challenge begins with mismatched incentives. Most physicians intend to do no harm and have a genuine interest in making sure their patients are not in pain. However, many are experiencing financial pressure due to the Affordable Care Act. According to CNN Money, reimbursement rates for Medicare have dropped anywhere from 35 to 40 percent. Considering half of physicians are in private practice and may be more sensitive to reimbursement changes, it makes office dispensing an attractive source of revenue to offset those declining rates.

Physician dispensing, when poorly practiced, costs insurers and could impact patient health. The Workers’ Compensation Research Institute (WCRI) found physician dispensing results in a 17 percent higher average total claim cost. WCRI found, for example, “injured workers in Florida, Georgia, Illinois, and Maryland paid physicians on average $4-to-$7 for a pill of ranitidine (Zantac), when they could have bought it at Walgreens for 33 to 42 cents, depending on the strength and quantity.” Medications may also be overprescribed. For example, an opioid may be prescribed when ibuprofen would help the patient manage their pain without the danger of addiction. Payers also need to be aware of up-charging and suspicious prescription patterns. In late 2015, the owner of Comprehensive Rx pleaded guilty to multiple anti-kickback violations for paying physicians and money laundering. Court documents revealed emails between the company and the physician including, "on or about April 14th of 2014, Dr. Ruan sent an email to Manfuso… 'You mentioned last week that you were concerned that Zofran got expensive. The price did go up a bit, but, it’s still a very profitable medication to dispense!'"

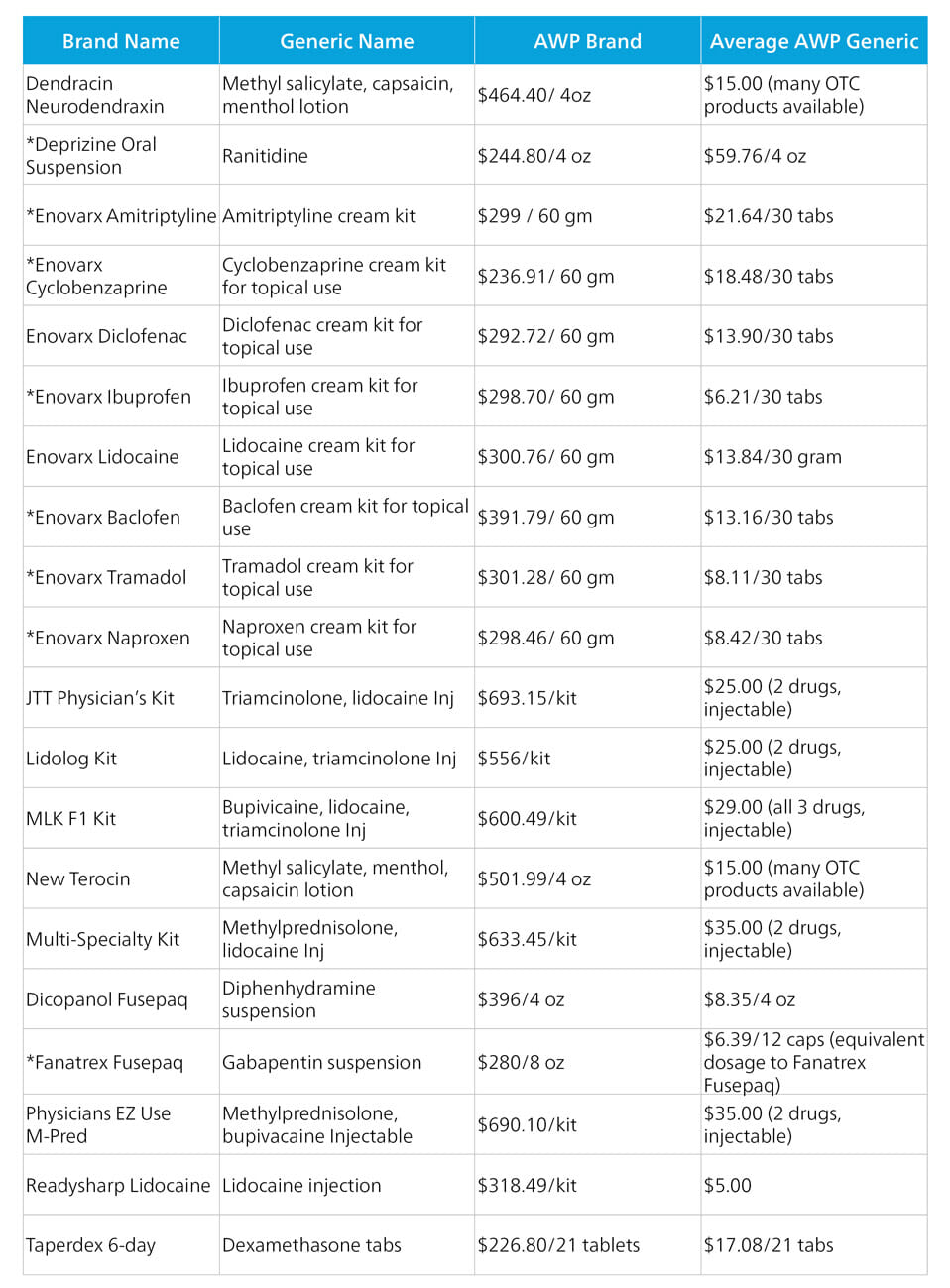

In addition to up-charging, physician-dispensed medications often bypass the formulary controls and best practices that have been put in place by insurers and Pharmacy Benefits Managers (PBMs). Bypassing adjusters and PBMs reduces their visibility into therapy trends and circumvents risk controls until much later in the life of the claim. One individual physician may be prescribing safely and well within limits, but the patient may ‘doctor shop’ to get a similar medication within the same period. If the dispensing is happening at doctors’ offices, then it may not be until at least a month later, when the bills are reviewed, that the adjuster would be able to see a potential pattern of abuse. Without the oversight, there may be little or no opportunity to both identify destructive patterns and intervene to help a patient. Interestingly, there are a number of medications that are specifically marketed to physicians for in-office dispensing. The medications are manufactured in kits, or different dosage formulations, then sent to physicians to use in their clinic and/or are sent home with the patient. Some of these medications include:

As shown, these medications are much more expensive than the average generic medication without any showing of increased efficacy. Ultimately, these kits and take-home medications provided in physician offices also increase the overall cost of workers’ compensation claims.

Best Practices

So how can we best support all stakeholders and ensure better outcomes for all? Below are some best practices that have been shown to be effective in curbing out-of-control prescribing practices as well as supporting the patient in their recovery.

1. Regulatory Support

There has been some progress on the regulatory front when it comes to physician dispensing. However, the results have yet to have the desired impact. WCRI found that the 2011 Florida law restricting physician-dispensed medication did not significantly influence the number of physician-dispensed medications. Rather, it moved physicians to prescribe medications with fewer restrictions. According to WCRI author Richard A. Victor, M.D.: “...specifically, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., ibuprofen)—from 24.1 percent to 25.8 percent, and the percentage receiving weaker (not banned) opioids increased from 9.1 percent to 10.1 percent. The findings from this study raise a concern that a significant proportion of pre-reform physician-dispensed strong opioids may not have been necessary, which means injured workers in Florida could have been put at greater risk for addiction, disability or work loss, and even death. Now policymakers might want to consider reforms that limit the use of physician dispensing in addition to reforms aimed at limiting the prices of physician-dispensed drugs.”

2. Communications and Monitoring

Regulatory solutions may not always be enough to change behavior or have the desired impact in the desired amount of time. Another avenue to combat physician-dispensed medication on later fills is to employ a data-driven approach. By leveraging access to available medical data, it is possible to identify physicians who have suspect prescribing patterns. Targeted physician communication programs can be effective in dissuading a network physician from continuing to dispense or alert them to unsafe practices that they may have unintentionally been employing. Additionally, informing physicians of doctor shopping behavior that they may not have had visibility into can be a lifesaving endeavor. Finally, an integrated Bill Review and PBM solution can provide formulary controls and risk monitoring to all prescriptions, including physician-dispensed medications. If high risk prescribing behavior is identified through bill review, then, regardless of where the drugs are dispensed, appropriate intervention can be made much earlier in the claim.

Want to learn more about medications that impact the workers' compensation industry? Read our article on combination medications.

Opioid Abuse

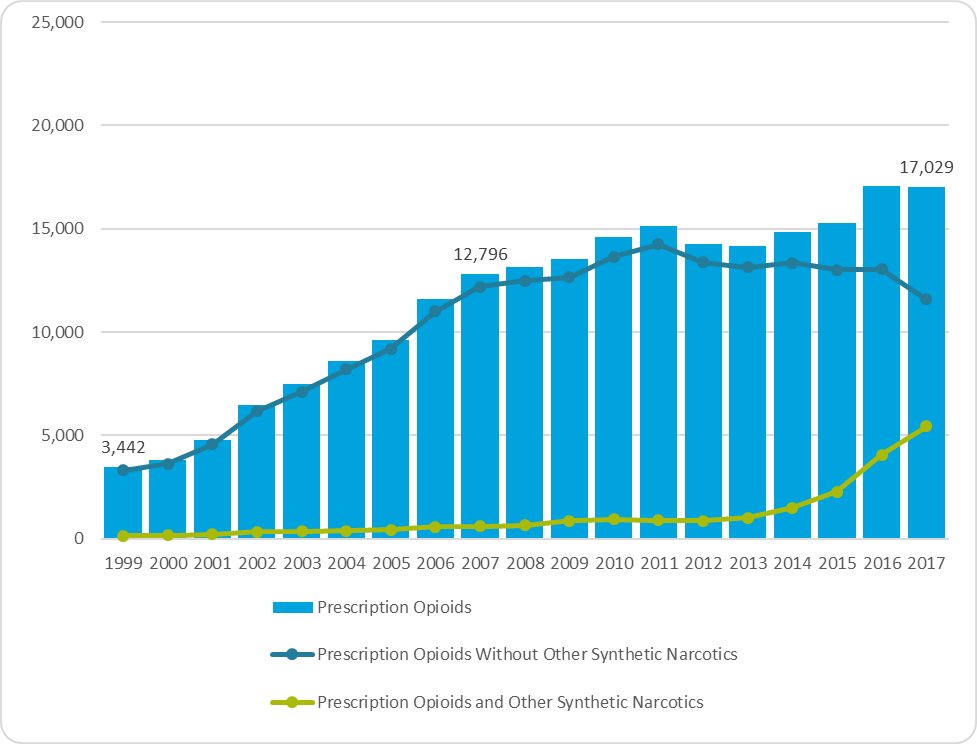

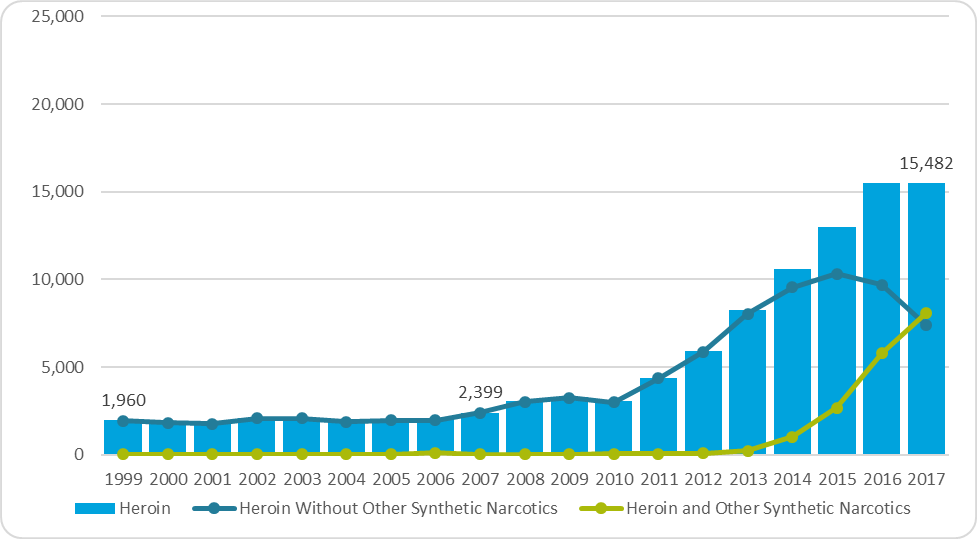

The second topic of perennial concern that has been in the national spotlight is opioid abuse. Over the last few years, the issue has spurred national conversations and action both inside and outside of the workers’ compensation and auto casualty space. Why? The latest report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sheds light on the severity of the issue: in 2017, there were nearly 48,000 overdose deaths associated with opioids, with more than 17,000 associated with prescription opioids. The opioid epidemic is not a new fight. Both federal and state governments have been working for years to try to curb overuse and abuse. In February 2016, The White House announced $1.1 billion in funding measures to address prescription opioid abuse, including opioid prescriber training and a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program expansion to 49 states. The report noted that an “estimated 20 percent of patients presenting to physician offices with non-cancer pain symptoms or pain-related diagnoses receive an opioid prescription.” There are 12 main recommendations or ‘best-practices’ that highlight physician and patient communication and common sense steps for prescribing these medications.

More recent efforts include opioid limits laws across various states, a federal omnibus bill to fight the opioid epidemic and a proposal by the DEA to reduce the opioid manufacturing quota for 2019. Many states are also taking steps to sue specific manufacturers of opioid medications. Purdue Pharma, in particular, is facing more than 1,600 lawsuits, with the first settlement occurring with the state of Oklahoma in March 2019. Awareness of the issue of opioid abuse has also prompted legislators to create closed workers’ compensation formularies in many states.

Alternative methods are also being considered, including the potential for medical marijuana to be prescribed in place of opioids for chronic pain. A few states, including Illinois, are considering programs to allow patients currently being prescribed opioids to instead use medical marijuana.

National Overdose Deaths

Number of Deaths from Prescription Opioid Pain Relievers

Number of Deaths from Heroin

Best Practices

1. Systems and Monitoring

A good first step in managing opioids is to have a robust and connected system that provides the necessary visibility into what medications claimants are being prescribed. Early intervention and the ability to apply formulary controls should begin at first fill at the point-of-sale, whenever possible. Systems should be in place to flag/alert adjusters immediately for prior authorization control, support step therapy, and let them appropriately manage the claim with access to prescription data. Some systems are also utilizing risk scoring reports and predictive modeling to identify patterns of behavior, such as doctor shopping, that are warning signs of unhealthy behavior.

2. Policies and Programs

Once claims are identified that require intervention, policies and programs should be implemented to provide support through the decision to intervene and the optimal course for intervention. Coordinating with internal teams and external partners to set up multidisciplinary groups can be effective as well as working directly with claimants on goal setting, pain management and abuse prevention strategies. A triage and support team can have a positive impact on the overall claim cost but, more importantly, on the life of your claimant.

Summary

Opioid abuse and physician dispensing are very serious problems that often stem from positive intentions–to help injured workers feel better faster. However, the unintended consequences can be dire. To successfully prevent, manage and solve drug therapy issues, three general capabilities are required: effective communications with all parties, visibility into all aspects of the claim data and having the right programs in place to effectively, efficiently and successfully intervene in the claim.