Study and Impact of Guidelines on the Workers’ Compensation Industry

Introduction

The United States is facing a very real and serious opioid epidemic. Prolific prescribing, widespread abuse, and the highly addictive nature of these drugs have contributed to rapid increases in opioid overdose deaths from both prescription opioids and its illegal counterpart, heroin. In response to this crisis, the first federal guidelines for the prescribing of opioids, Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain (CDC Opioid Guidelines), were published in March of 2016. National opioid epidemic impacts workers’ compensation Pain is the most prominent symptom treated with medications following a work-related injury. As a result, the workers’ compensation industry has felt the impact of opioid use more directly than other insurance markets involved in healthcare delivery. In this white paper, we will explore:

- How the prescribing of opioids for the treatment of pain led to the epidemic in America

- What conditions were present to support the rapid increase in opioid prescribing

- Review the impact on the health and well- being of the general public

- Provide an overview of the CDC Opioid Guidelines

- Through an in-depth data analysis, provide insight into the state of opioid prescribing in workers’ compensation prior to and after release of the CDC Opioid Guidelines

- Discuss how industry stakeholders will be impacted should the CDC Opioid Guidelines, at some point, be enforceable through regulation

An Opioid Epidemic

We are a nation with a drug culture. Specifically, we are a nation that loves prescription drugs. Representing only 5% of the world’s populations, the U.S. consumes 75% of the prescription drugs on this planet. In 2012, 259 million opioid prescriptions were written. That would be enough opioids to supply every adult in the U.S. their own prescription bottle.  Opioids are highly addictive substances. An oversimplified way to view the rise of the opioid epidemic is in terms of numbers. Logically, if vast amounts of opioids are prescribed, a certain percentage of individuals will become addicted or abuse these medications. Of those that become addicted or abuse opioids, a certain number will overdose. Of those that do overdose, a certain number will die.

Opioids are highly addictive substances. An oversimplified way to view the rise of the opioid epidemic is in terms of numbers. Logically, if vast amounts of opioids are prescribed, a certain percentage of individuals will become addicted or abuse these medications. Of those that become addicted or abuse opioids, a certain number will overdose. Of those that do overdose, a certain number will die.

By the Numbers

The following statistics provide insight into the scale of that logical path:

- Greater than 15 million people in the U.S abuse prescription drugs

- 52 million Americans have used prescription drugs non-medically (i.e. recreationally)

- Over 52% of prescription drug abusers report getting the drugs for free from a friend or relative

- Heroin use was up 75% from 2007 – 2011

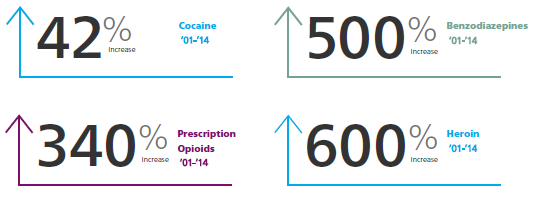

Not surprising, the statistics related to overdose deaths have followed an escalating trend from 2001 to 2014 in overdose deaths.

In 2015, more than 52,404 people died from drug overdoses and opioids were involved in 52% of those deaths. For context, automobile related deaths were 37,757 in 2015. Overall drug spend in the workers’ compensation industry is estimated to be $5.5 billion annually. Of that spend, 50% of prescriptions are for the treatment of pain and 70% of those are opioids.

In 2015, more than 52,404 people died from drug overdoses and opioids were involved in 52% of those deaths. For context, automobile related deaths were 37,757 in 2015. Overall drug spend in the workers’ compensation industry is estimated to be $5.5 billion annually. Of that spend, 50% of prescriptions are for the treatment of pain and 70% of those are opioids.

How Did We Get Here?

Until the late 1970’s, physicians were hesitant to prescribe opioids to patients experiencing pain. Widespread apprehension about the addictive nature of these drugs existed throughout the medical community. Throughout the 1980’s, an opposing concern began to emerging among treating physicians, the under treatment of pain. By the late 1980’s, the medical community’s concern with the under treatment of pain created the perfect storm as medical literature was published relieving fears around the addictive nature of opioids. In 1980, Jane Porter and Hershel Jick published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine titled, “Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics.” In 1986, pain-management specialist Dr. Russell Portenoy published, “Chronic Use of Opioid Analgesics in Non-Malignant Pain: Report of 38 Cases” in the journal Pain. These and other publications shifted the perspective of treating physicians from one of apprehension of opioids to becoming the drug class of choice in the treatment of moderate to severe pain. Corresponding with a new commitment to treat pain with opioids, pain was now considered the “Fifth Vital Sign”, trademarked by the American Pain Society in 1996 and adopted by the Veteran’s Administration in 1998. The four other vital signs, body temperature, pulse rate, respiration rate, and blood pressure are objectively measured. The new vital sign, pain, was to be subjectively measured as the level of pain the patient communicated they were experiencing. If a patient states they are in pain, they are in pain. Mitchell looks at prescriptions Drug manufacturers quickly took advantage of shifting sentiments around opioid prescribing. Perdue Pharma released OxyContin in 1996. Dr. Portenoy’s research received millions of dollars in funding from drug manufacturers including Perdue Pharma (manufacturer of OxyContin®), Endo (manufacturer of Percocet®), and Cephalon (manufacturer of Actiq®). Perdue Pharma released a patient education video distributed in physician’s offices entitled, “I Got My Life Back”, in 1998. Opioid prescriptions increased by 11 million the following year. In 2007, Purdue Pharma and three executives were charged with misleading physicians and the public about the addiction risks of OxyContin. The company paid $600 million in fines. The executives plead guilty and paid a combined $34.5 million in fines.

National and Industry Response

From a national perspective, the prescription opioid and heroin epidemic cannot be detached from each other. Four out of five new heroin users report abusing prescription opioids prior to moving on to heroin. The primary reason for the transition to heroin was that heroin is cheaper and easier to obtain than prescription opioids. The progression from prescription opioid addiction to heroin use is a devastating component of this epidemic and will need to be addressed on a national level.  As an industry, workers’ compensation has responded to the opioid prescription epidemic. State legislation has been passed with Utah and Washington leading the way early in the crisis. In addition, independent organizations like the Official Disability Institute (ODG) published by the Work Loss Data Institute and The American College of Occupational & Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) have released industry specific guidelines for prescribers in the appropriate use of opioids for the treatment of pain specific to workplace injuries. Heroin users may start with prescription drugs In some instances, these guidelines have been adopted into state regulation, providing not only recommendations for appropriate treatment of pain, but the legislative backed leverage to enforce it. Pharmacy Benefits Managers (PBMs) are almost universally utilized by payors as partners in controlling inappropriate opioid prescribing. Outside of the workers’ compensation system, several states have passed legislation limiting the daily allowable dose and days supply of opioid prescriptions. On a national basis, President Obama’s attendance at the 2016 National Rx Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit was a call to establish the first federal guidelines for opioid prescribing and provide funding for opioid addiction treatment. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 was signed, providing state support for expanding Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), providing funding for Naloxone use to treat emergency opioid overdose, and increasing education and prevention efforts. However, many stakeholders feel the bill failed to provide for extensive opioid addiction treatment.

As an industry, workers’ compensation has responded to the opioid prescription epidemic. State legislation has been passed with Utah and Washington leading the way early in the crisis. In addition, independent organizations like the Official Disability Institute (ODG) published by the Work Loss Data Institute and The American College of Occupational & Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) have released industry specific guidelines for prescribers in the appropriate use of opioids for the treatment of pain specific to workplace injuries. Heroin users may start with prescription drugs In some instances, these guidelines have been adopted into state regulation, providing not only recommendations for appropriate treatment of pain, but the legislative backed leverage to enforce it. Pharmacy Benefits Managers (PBMs) are almost universally utilized by payors as partners in controlling inappropriate opioid prescribing. Outside of the workers’ compensation system, several states have passed legislation limiting the daily allowable dose and days supply of opioid prescriptions. On a national basis, President Obama’s attendance at the 2016 National Rx Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit was a call to establish the first federal guidelines for opioid prescribing and provide funding for opioid addiction treatment. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 was signed, providing state support for expanding Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), providing funding for Naloxone use to treat emergency opioid overdose, and increasing education and prevention efforts. However, many stakeholders feel the bill failed to provide for extensive opioid addiction treatment.

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain

In March of 2016, the CDC published the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. The CDC‘s stated goal was to improve communication between providers and patients about the risks and benefits of opioid therapy for chronic pain, improve the safety and effectiveness of pain treatment, and reduce the risks associated with long-term opioid therapy, including opioid use disorder and overdose. The guidelines apply only to adults and do not apply to patients experiencing cancer related pain, palliative care, or end of life care. Although the guidelines were written for the use of opioid therapy in treating chronic pain, many patients experiencing acute pain are treated with opioids. For many patients, acute pain typically precedes chronic pain. Therefore, portions of the CDC Opioid Guidelines are applicable to acute pain and some components are specifically written for the treatment of acute pain. Prescriber education materials were also produced in conjunction with the guideline release. Reminders for prescribers in these materials include:

In March of 2016, the CDC published the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. The CDC‘s stated goal was to improve communication between providers and patients about the risks and benefits of opioid therapy for chronic pain, improve the safety and effectiveness of pain treatment, and reduce the risks associated with long-term opioid therapy, including opioid use disorder and overdose. The guidelines apply only to adults and do not apply to patients experiencing cancer related pain, palliative care, or end of life care. Although the guidelines were written for the use of opioid therapy in treating chronic pain, many patients experiencing acute pain are treated with opioids. For many patients, acute pain typically precedes chronic pain. Therefore, portions of the CDC Opioid Guidelines are applicable to acute pain and some components are specifically written for the treatment of acute pain. Prescriber education materials were also produced in conjunction with the guideline release. Reminders for prescribers in these materials include:

- Opioids are not first-line or routine therapy for chronic pain

- Establish and measure goals for pain and function

- Discuss benefits and risks and availability of non-opioid therapies with patient

- Use immediate-release opioids when starting

- Start low and go slow

- When opioids are needed for acute pain, prescribe no more than needed

- Do not prescribe ER/LA opioids for acute pain

- Follow-up and re-evaluate risk of harm; reduce dose or taper and discontinue if needed

In addition to the reminders above, specific quantifiable recommendations are provided relating to the choice of opioid agents, dosing ranges to adhere to, cautions against certain drug combinations, and the duration of therapy (i.e. the number of days supply).

Prescribe No More Than Needed

Opioid therapy is frequently initiated for the treatment of acute pain. When beginning opioid therapy, the shortest duration necessary should be used. The CDC states that a three-day supply of opioids is often adequate and it is rare that more than seven days are required.

Use Immediate Release Formulations to Start

When beginning opioid therapy, immediate release opioids should be used first. Immediate release formulations include Lortab and Percocet. These agents can be taken for breakthrough pain, allowing patients to take only as needed when the pain is intolerable. Long acting opioids such as OxyContin and Zohydro, release a steady dose over long periods of time resulting in delivery of opioid long after the breakthrough pain has subsided.

Use the Lowest Effective Dose

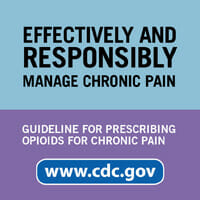

When initiating opioids, the lowest possible dose resulting in relief should be used. The CDC provides recommendations on daily dose thresholds based on the Milligrams of Morphine Equivalent per Day (MME/day), sometimes referred to as Morphine Equivalent Dosing (MED) or Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD). The CDC states that risks should be carefully assessed before increasing total daily dosing above 50 MME/day and to avoid prescribing more than 90 MME/day.

Do Not Prescribe Long Acting Opioids for Acute Pain

Long Acting Opioids should only be used in patients experiencing chronic pain and only after carefully assessing the associated risk.

Avoid Concurrent Prescribing of Benzodiazepines and Opioids

The concurrent use of Benzodiazepines (Xanax, Ambien) and Opioids are associated with significant risk of overdose and death. 30% of opioid overdose deaths in recent years were associated with concurrent use of benzodiazepines.  Unlike recommendations intended to facilitate discussion between provider and patient concerning risks and establishing goals around opioid therapy, the above recommendations are distinctly measurable by insurers, PBMs, and managed care organizations within the workers’ compensation industry. Identifying opioid prescribing outside of the CDC recommendations and intervening with prescribing physicians presents an opportunity to avoid unnecessary risks and promote better outcomes for injured workers. Clinical guidelines are recommendations to guide the medical community, insurers, and other stakeholders in the healthcare delivery system toward appropriate treatment and optimal outcomes. Guidelines by themselves are not enforceable and do not ensure appropriate treatment. However, many state regulations reference guidelines such as ODG and ACOEM in their legislations which is enforceable.

Unlike recommendations intended to facilitate discussion between provider and patient concerning risks and establishing goals around opioid therapy, the above recommendations are distinctly measurable by insurers, PBMs, and managed care organizations within the workers’ compensation industry. Identifying opioid prescribing outside of the CDC recommendations and intervening with prescribing physicians presents an opportunity to avoid unnecessary risks and promote better outcomes for injured workers. Clinical guidelines are recommendations to guide the medical community, insurers, and other stakeholders in the healthcare delivery system toward appropriate treatment and optimal outcomes. Guidelines by themselves are not enforceable and do not ensure appropriate treatment. However, many state regulations reference guidelines such as ODG and ACOEM in their legislations which is enforceable.

Industry Compliance

Considering the current national focus on the opioid epidemic, it is possible that the CDC Opioid Guidelines could, at some point, become enforceable on a national level. If the Guidelines were enforceable, what impact could be expected to the workers’ compensation industry? How compliant was opioid prescribing at the time of CDC Opioid Guidelines publication? Has there been any measurable change since the CDC Opioid Guidelines were introduced? What impact would enforcing the CDC Opioid Guidelines have on injured workers currently being treated, treating physicians, insurers, PBMs, and managed care organizations?

Study Methodology

To answer these questions, Mitchell conducted a retroactive analysis of more than 815,000 workers’ compensation claims with a date of injury after 1/1/2011. This included a corresponding 3.9 million prescriptions. The study population was further limited to claimants receiving an opioid prescription resulting in a final study population of greater than 417,000 claimants receiving more than 1,059,000 prescriptions. Compliance to CDC Opioid Guidelines were assessed against the five aforementioned, measurable CDC recommendations, with the following criteria for evaluation:

Compliance with the above criteria were analyzed for two distinct groups, claimants with dates of injury prior to release of the CDC Opioid Guidelines and those with date of injury after release of the CDC Opioid Guidelines. In this evaluation, the release of the CDC Opioid Guidelines was considered to be March 17, 2016.

Results

RECOMMENDATION 1

Prescribe no more than needed. Greater than a 7 day supply of the first opioid is rarely warranted.

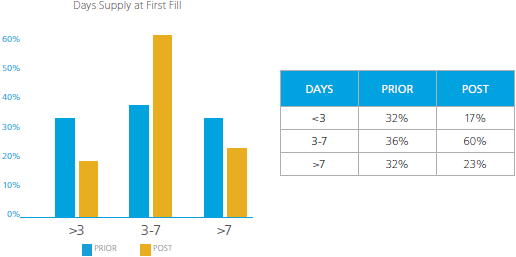

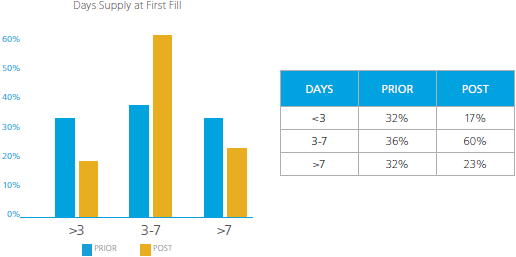

For the population receiving their first opioid prescription prior to the CDC Opioid Guidelines release, there was a fairly even distribution of days supply among the less than three (<3) days supply, 3-7 days supply, and those receiving greater than seven (>7) days supply. It is concerning that prior to the CDC Opioid Guidelines release, 32% of claimants received greater than a 7 days supply for their first opioid prescription. The results showed improvement in the percentage of claimants receiving greater than seven (>7) days supply, a reduction from 32% to 23%. However, there was a reduction in the percentage of claimants receiving less than three (<3) days supply from 32% to 17%. The reduction of the <3 and >7 groups appear to have shifted to the 3-7 days supply groups, an increase from 36% to 60%. Even taking these shifts in days supply into account, 23% of claimants are receiving an initial opioid prescription with a days supply greater than seven days, rarely necessary according to the CDC. It is of interest to note that upon further analysis, OxyContin appeared as number 10 of the top 10 drugs written for greater than seven days supply as the first opioid prescription in the population of claimants prior to the CDC Opioid Guidelines’ publication. In this population, OxyContin comprised 0.6% of the prescriptions written for greater than 7 days supply. Only short acting opioids appeared in the top 10 drugs prescribed after the guidelines were published.

For the population receiving their first opioid prescription prior to the CDC Opioid Guidelines release, there was a fairly even distribution of days supply among the less than three (<3) days supply, 3-7 days supply, and those receiving greater than seven (>7) days supply. It is concerning that prior to the CDC Opioid Guidelines release, 32% of claimants received greater than a 7 days supply for their first opioid prescription. The results showed improvement in the percentage of claimants receiving greater than seven (>7) days supply, a reduction from 32% to 23%. However, there was a reduction in the percentage of claimants receiving less than three (<3) days supply from 32% to 17%. The reduction of the <3 and >7 groups appear to have shifted to the 3-7 days supply groups, an increase from 36% to 60%. Even taking these shifts in days supply into account, 23% of claimants are receiving an initial opioid prescription with a days supply greater than seven days, rarely necessary according to the CDC. It is of interest to note that upon further analysis, OxyContin appeared as number 10 of the top 10 drugs written for greater than seven days supply as the first opioid prescription in the population of claimants prior to the CDC Opioid Guidelines’ publication. In this population, OxyContin comprised 0.6% of the prescriptions written for greater than 7 days supply. Only short acting opioids appeared in the top 10 drugs prescribed after the guidelines were published.

Discussion of Results

This study was intended to be an evaluation of the workers’ compensation industry as it relates to CDC Opioid Guidelines compliance prior to and after the publication of the CDC Opioid Guidelines. The influence of numerous other factors on the prescribing habits of prescribers could not be accounted for in this study. Insurers, PBMs, and managed care organizations have continued to make gains in opioid intervention. Quantification of how industry specific guidelines and state regulations have impacted prescribing habits also cannot be accounted for in this study. Regardless of the relatively positive changes seen since publication of the CDC Opioid Guidelines, a very significant percentage of claimants continue to be subjected to high risk opioid prescribing.

What Can Insurers Do?

Most payors rely on PBMs to assist in managing opioid prescriptions through network discounts as well as clinical management. Opioid guidelines, whether from the CDC or other agencies and organizations, help to ensure injured worker safety, promote better outcomes, and lower overall claims cost. As opioid guidelines become more enforceable over time (through industry adoption or legislation), PBMs need to have dynamic pharmacy claims management systems, earlier visibility into medications prescribed for the claimant, and comprehensive insight into all injury related prescriptions for the injured worker.

Step 1: Plan for Success

Before any worker is ever injured, insurers have the opportunity to set up their programs for success. The first step is to create robust, injury-specific, dynamic formularies that take the CDC Opioid Guidelines and/or additional regulations into account. Doing so will help both the PBM and the adjustor make the best decision at critical points in the claim.

Integrate Managed Care Best Practices Into Your Program

Managed care is a critical component of an insurers’ opioid management strategy. Insurers have the opportunity to craft a plan that includes best-practices such as early-claim education programs for families and claimants as well as integration with the claims process so all recommendations are fed back into the decision making on a claim. Additionally, managed care triggers should be set up based on risk alerts to quickly get claimants the support they need. Triggers could result in actions such as a pharmacist review based on drug combinations or a peer-to-peer conversation based on prescribing behavior. Managed care for opioid use should also include plans for how best to support those claimants who have become addicted to opioids during their recovery.

Step 2: Identify Challenges and Opportunities with Partners

The CDC Opioid Guidelines (as well as other guidelines) defines limits to the duration of the first opioid prescription, recommends that immediate release formulations be used, and places limits on the dosing of opioid prescriptions. Therefore, to support insurer adoption of such guidelines, PBM claims management systems must recognize the first opioid prescription and ensure that the prescription meets these dosing, duration, and formulation requirements. The system must then be flexible enough to adjust to subsequent prescriptions as changes in the claim occur.

Challenge: First Opioid Fill Visibility

Specifically, the CDC Opioid Guidelines place recommendations on the first opioid prescription. This is a challenge for many PBMs as they do not always have visibility into the first prescription filled post-injury. These prescriptions are frequently obtained even before a claim has been reported to the insurer.  Having visibility into these ‘first fills’ is essential in enforcing appropriate opioid management in accordance to prescribing guidelines. Insurers can work with their PBM to ensure that first-fills are being captured by identifying their leakage and then establish programs to acquire those first fills of opioids as well as manage them with clinical controls such as blocks and prior authorizations.

Having visibility into these ‘first fills’ is essential in enforcing appropriate opioid management in accordance to prescribing guidelines. Insurers can work with their PBM to ensure that first-fills are being captured by identifying their leakage and then establish programs to acquire those first fills of opioids as well as manage them with clinical controls such as blocks and prior authorizations.

Challenge: Total MED Visibility

Additionally, to evaluate the total daily dose of opioids prescribed, the PBM must have full visibility into all prescriptions the claimant is receiving. This is another challenge for many PBMs as they do not typically capture all prescriptions. Prescriptions may not be visible to a PBM because they were not identified at the point-of-sale and subsequently paper billed by the pharmacy. This circumvents the controls at the point-of-sale and makes it difficult to re-capture that prescription data into the system.  In the event that prescriptions are unaccounted for, the MME/day calculation will be understated. This may lead to an underestimation of risk and missed opportunities to identify and intervene on claims that do not comply with opioid prescribing guidelines. Insurers can support this improved visibility across the claim by integrating bill review and PBM systems to have a universal view of all the prescriptions a claimant is receiving. Only then, can the PBM make accurate risk assessments to keep the claim in compliance and avoid harm.

In the event that prescriptions are unaccounted for, the MME/day calculation will be understated. This may lead to an underestimation of risk and missed opportunities to identify and intervene on claims that do not comply with opioid prescribing guidelines. Insurers can support this improved visibility across the claim by integrating bill review and PBM systems to have a universal view of all the prescriptions a claimant is receiving. Only then, can the PBM make accurate risk assessments to keep the claim in compliance and avoid harm.

Summary

In a country facing a major epidemic of opioid addiction, the workers’ compensation industry has a role to play. It is in a unique position to continue to take the best-practice recommendations, such as the CDC Opioid Guidelines, to craft programs that support claimant health during and after injury recovery. While it is clear from the data that many of these recommendations are already happening today, a percentage of claimants are still at risk of becoming addicted to the very medicine designed to help them. Therefore, it is critical that insurers both build the right programs and partner with solution providers to correctly identify and support claimants who may be at risk. By selecting a PBM partner with the ability to plan for success as well as have the technology and solution capabilities to manage the complexities of prescribing guidelines, insurers and their claimants can achieve measurably better outcomes.

About Mitchell ScriptAdvisor

Integrated | Experienced | Exclusively P&C

Mitchell ScriptAdvisor™ is the PBM solution that leverages technology and industry expertise to connect the ENTIRE claim. Mitchell’s pharmacy benefit management solution was built exclusively for auto and workers’ compensation payers. It delivers a holistic view to drive data-driven decisions that deliver better outcomes for you and your claimant. Mitchell ScriptAdvisor simplifies, manages, and supports pharmacy benefits as part of a solution set that looks across all aspects of the claim to effectively, efficiently, and successfully manage with integrated solutions including managed care and bill review. ScriptAdvisor provides you the visibility beyond an individual prescription to the wider spectrum of insights so you can make the decision that gets your claimant back to their lives faster. For more information, please visit mitchell.com/scriptadvisor or contact us at 877.750.0244.