The CDC and P&C: New Opioid Guidelines a Powerful Step in the Right Direction

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) newly established guidelines for the prescribing of opioids for chronic pain. These guidelines provide clear recommendations for treating physicians that prior to now have been ambiguous at best. Opioid medications represent a significant cost to the Property and Casualty (P&C) industry. The direct cost of these drugs as well as the indirect cost associated with poor outcomes due to overuse, misuse, and abuse of opioid medications can be significant. This article will discuss a brief overview of the new CDC opioid guidelines and the potential impact that guidelines will have on the P&C Industry.

Injuries and Pain

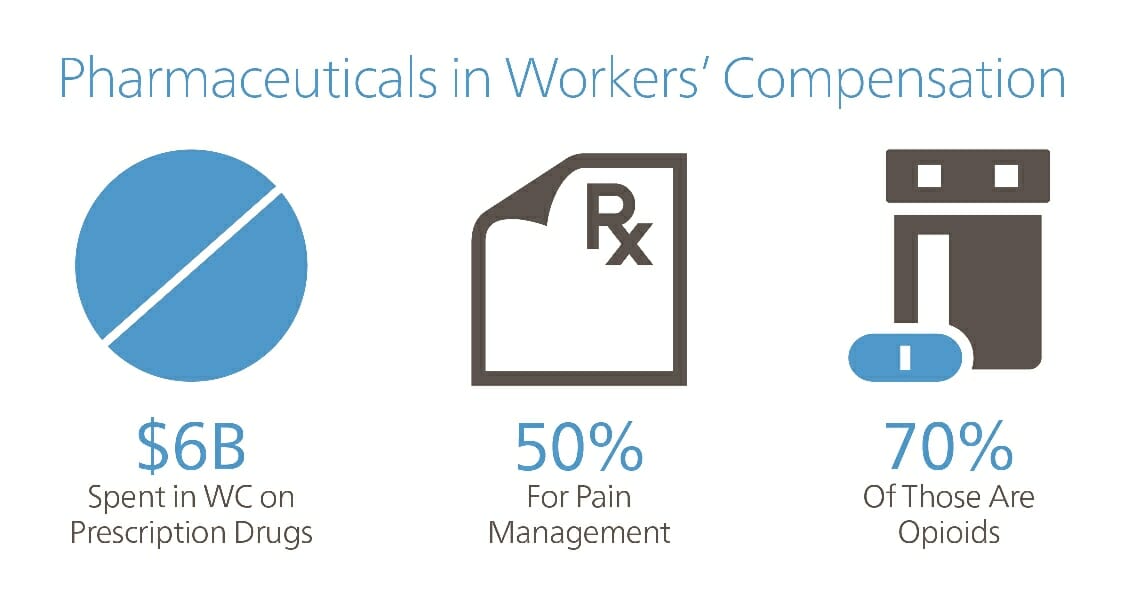

Most prescription drug expenditure in the P&C industry is associated with the treatment of automobile injuries and injuries occurring at work, Workers’ Compensation (WC). Due to varying state regulations and policy limits in the auto market, definitive numbers for overall drug costs are difficult to obtain. In the WC market, it is estimated that well over $6 billion is spent on prescription drugs on an annual basis, representing approximately 19% of overall medical cost. Despite not being first line therapy for the treatment of pain, opioids are commonly prescribed for newly injured individuals. Approximately 70% of pain drugs prescribed are opioids representing almost a third of overall prescriptions. Individuals using opioids over an extended time may experience tolerance, meaning a higher does is needed to obtain the same level of pain relief. This often leads to escalating doses of opioid over time. Higher doses for extended periods are associated with higher rates of dependence, higher rates of addiction, poor health outcomes, and significantly higher claims cost. An opioid addicted person will experience withdrawal symptoms when the prescribed dose is significantly reduced or stopped by the prescribing physician.

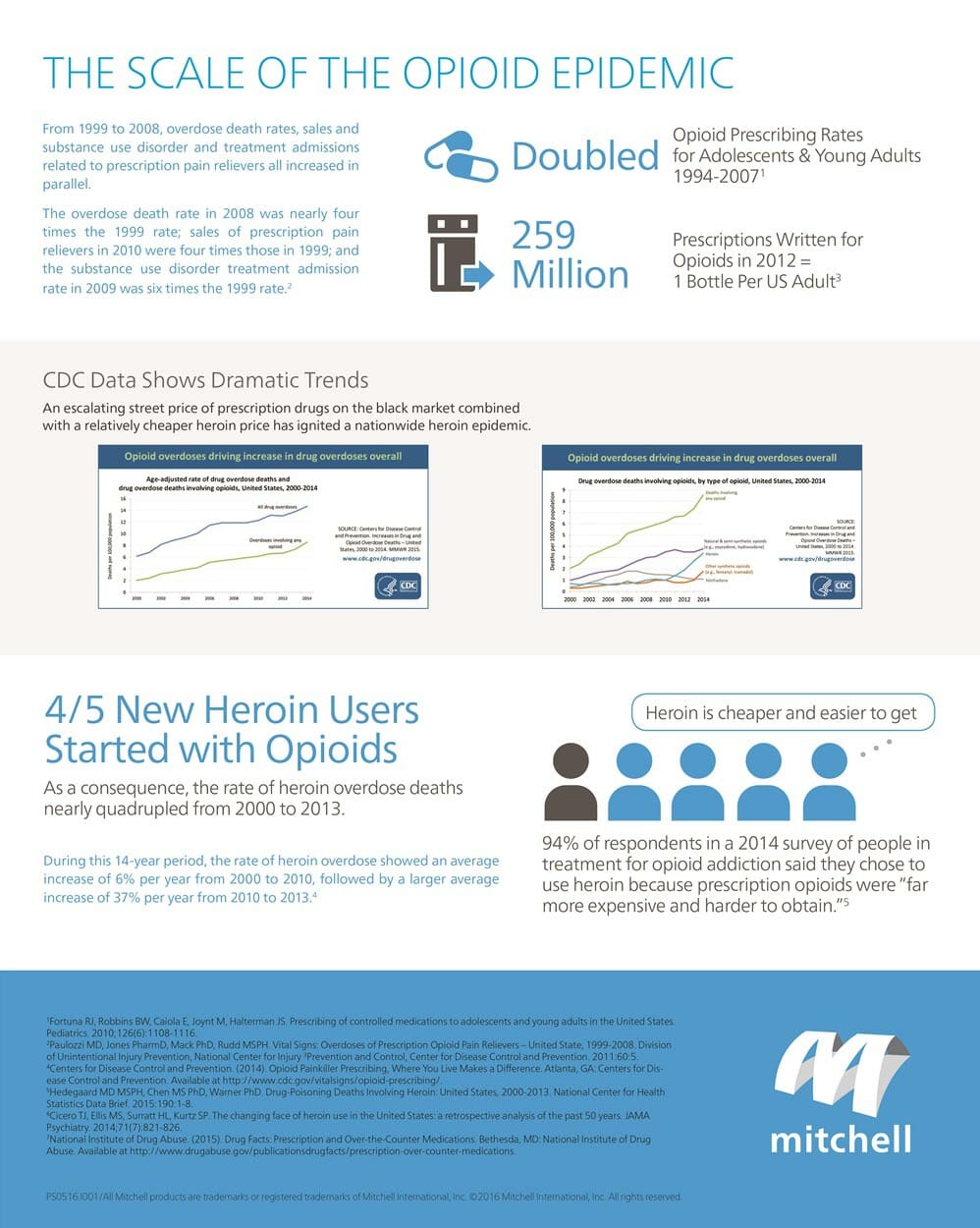

An Epidemic

The intense desire to avoid withdrawal symptoms can lead to drug seeking behavior outside of a patient/prescriber relationship, purchasing prescription opioids on the street. An escalating street price of prescription drugs on the black market combined with a relatively cheaper heroin price has ignited a nationwide heroin epidemic. Recent spikes in abuse and overdoses have catapulted the topic into the public eye. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated in January that, ‘“there is a need for continued action to prevent opioid abuse, dependence and death.” [i] According to the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, there were a “record number of drug-related deaths in 2014, with 61% from some kind of opioid.”[ii] In February 2016, The White House announced $1.1 billion in funding measures to address prescription opioid abuse including opioid prescriber training and a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program expansion to 49 states. [iii] The report noted that an, “estimated 20 percent of patients presenting to physician offices with non-cancer pain symptoms or pain-related diagnoses receive an opioid prescription."[iv]

CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain

In conjunction with the White House initiatives, the CDC published guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain in March 2016. The guidelines apply to adult patients with chronic pain (longer than 3 months) and do not apply to patients receiving cancer treatment, palliative care, or end-of-life care. A high level summary of the main components of the guidelines include:

- Opioids are not first-line or routine therapy for chronic pain.

- Establish and measure goals for pain and function.

- Discuss benefits and risks and availability of nonopioid therapies with patient.

- Use immediate-release opioids when starting (not OxyContin, MS Contin, or fentanyl patches).

- Start low and go slow. Carefully assess risks when prescribing over 50 morphine milligram equivalents/day and avoid dosing over 90 morphine milligram equivalents/day.

- When opioids are needed for acute pain, prescribe no more than needed. Do not exceed a 3 days or less, rarely greater than 7 days is needed.

- Do not prescribe ER/LA (OxyContin, MS Contin, or fentanyl patches) opioids for acute pain.

- Follow-up and re-evaluate risk of harm; reduce dose or taper and discontinue if needed.

- Evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms.

- Check PDMP (Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs) for high dosages and prescriptions from other providers.

- Use urine drug testing to identify prescribed substances and undisclosed use.

- Avoid concurrent benzodiazepine and opioid prescribing.

- Arrange treatment for opioid use disorder if needed.

Potential Impact of Guidelines on WC and Auto Market

With prescription drug costs comprising approximately 19% of total medical costs in WC, significant reductions in claim costs can be achieved in overall medical costs by addresses pharmacy spend. Most of the drug cost in WC and auto is driven by opioid prescribing for the treatment of chronic pain. Frequently, pain medications for these claimants can run thousands of dollars per month. Much of the chronic opioid use in chronic pain is avoidable early in the claim, during the accuse phase shortly after injury. By preventing therapy for acute injuries from progressing in to long term, chronic opioid pain therapy claims, much of the eventual opioid cost can be avoided. Because chronic opioid therapy is associated with delayed return to work, poor outcomes, and higher non-pharmacy medical costs, overall claims cost could be significantly reduced. The CDC guidelines are appropriately focused to address the high risk use of opioid therapy. Pharmacy Benefits Managers (PBMs) in the P&C industry have known for years that higher doses of opioids, early use of long-acting opioids, and lack of effective monitoring with tools such as urine drug monitoring, are risks that correlate with high future drug spend. Implementing these guidelines should have a significant positive effect on controlling inappropriate opioid prescribing. However, the guidelines are currently only guidelines, not regulations. At this time, it is not yet known how enforceable they will be. Payor’s ability to apply the guidelines without regulatory support will be critical. Regardless, the CDC Guidelines are a powerful step in the right direction.